This was one of my favorite essays to write! I’m happy to share it again — or maybe for the first time, for those who have joined my email list since it “aired” a year or so ago.

I will be wrapping up my Lenten retrospectives with a brand-new piece next week in time for the Resurrection Feast. Stay tuned!

I lay my hands on the garden soil gently turned into the melting snow and whisper to my smaller son: shall we bless our garden in God’s name? Ya! he responds with exuberance while grabbing clods of soil and flinging them across the sidewalk I’d just come from sweeping. I calm the heart-jerk to…to…to freak out. Do I chew him out for doing it again? (It was again.) Or lead gently? It always seems obvious in retrospect which choice is better but I often teeter on the edge, in the throes of my own expectations, irritation, and whatever neat little story I am trying to tell. Then it occurs to me, one possible reason why the soil didn’t stay within bounds. Maybe my garden was too small. I was trying to exercise control over matter which always has a life of its own. His voice breaks into my thoughts. Is it Christmas, mama? Is it Easter? Is it spring? What does it mean, spring? I gather him up, my son of earth, and assure him. It’s finally spring, baby. And spring is when all is soft again.

Endure the long game but don’t let the heart get obdurate. The name of the long game is Love.

Recently Caroline Ross wrote in her substack about the mineral vestiges left behind in the earth, that which she seeks out in fashioning her own art materials:

The chalk that I love to make paint with is the compressed, long dead bodies of creatures who were here before me under the water. So there's death and difficulty again, they're just part of life. If we can move with Grace through difficulty, we played the game well. We played our part.

The fossilized pain will now be crushed again, but into flowing colors which will participate freshly in the realities of Creation. Beautifully, her words came to me directly after my teacher had handed me a prayer written by Jesuit theologian and scientist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. This is a man who knew his fossils too and also spent a lot of time trying to connect their story with that of God’s ongoing, creative work in evolution. His words now vibrated anew:

Above all, trust in the slow work of God.

We are quite naturally impatient in everything,

To reach the end without delay.

We should like to skip the intermediate stages.

We are impatient of being on the way

to something unknown,

something new.

And yet it is the law of all progress

That it is made by passing through

Some stage of instability—

And that it may take a very long time.

And so I think it is with you;

Your ideas mature gradually — let them grow,

Let them shape themselves, without undue haste.

Don’t try to force them on,

As though you could be today what time

(that is to say, grace and circumstances acting on your own good will)

Will make of you tomorrow.

Only God could say what this new spirit

Gradually forming in you will be.

Give Our Lord the benefit of believing

That his hand is leading you,

And accept the anxiety of feeling yourself

In suspense, and incomplete.

Such tongue-in-cheek cheekiness. To give our Lord the benefit of the doubt! But how right to do so. His inimitable way of mystically and scientifically viewing the summing up of all things in Christ links the millennia-long development of biological organisms to the new growth of our hearts from stone to fleshy newness. I love it.

And as if the cosmic Christ himself were also connecting himself to the ebb and flow of items at our local thrift store (I do not doubt it), they were giving away religious books during Holy Week and look what happened to be there in the pile:

I wonder. What will the vestigial bits of my current sufferings render ten years from now, twenty years from now? Will they even be perceptible to me in this life? Is it only for others to discover or leave undiscovered? It’s the enduring timeline we don’t expect. A duration in the millions and billions. It seems interminable and includes instability and pain and maybe even transitional forms (!) in the evolution of our hearts. One wonders what portion of trilobites, sharks’ teeth and dinosaur bones are simply secrets of the earth, never to be known. And so with our own hopes and fears.

Above all, trust in the slow work of God.

Maybe it’s all transition and flow, as evolutionary biology describes. It’s just happening so slowly that we think that there is one form of something. One form of love, one form of this relationship with this person, one form of church, one form of understanding this or that. Lent is over for now, but I’m reminded how it shares origins with the word lengthening. I’ve been lentening my days. New disciplines to me, old as the hills, serve to stretch my Heart and the Moment. And someday the new wine will pour into these new wineskins. Maybe it’s already coming, a trickle at a time.

The birds were mad with joy on Holy Saturday. The squee squee of every sparrow and robin throated out in perfect reedy fashion. They sang the praises of the rescuer resting in his tomb. Are you sad? they sang. Do you ache? Just you wait. Till tomorrow.

It seems fitting now that we ended up watching Song of the Sea at home right before the Great Easter Vigil on Saturday. The film begins with a family bent over like the trees near the lighthouse where they live. They’ve been calcified into that form by pain, due to the early loss of a mother and wife. The shape of the mother haunts Ben and makes him resentful towards his little sister. The father is distant, vacant. The little girl, Saoirse, is the only one who pushes into the depths of the sea to come to terms with their family’s story. Initially, Ben refuses but he is dragged, literally, by his sister down a gloomy holy well and into the depths of his own consciousness where he faces memories of his mother, grandmother, and the ways he’s mistreated his sister. The journey that the two siblings take is transformative and because it is a movie (and there’s significant magic involved), these changes are lightning-fast, in contrast to Teilhard’s long game. There are hints in Ben and Saoirse’s quest that all of this work of the Heart does take awhile to mature. But it’s also good to remember that grace in our own life story really does enact something like evolutionary leaps sometimes. Maybe that’s a kind of magic. (It sure feels like it.)

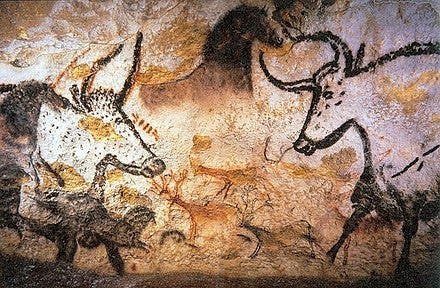

My thoughts return to the garden, my desire to be as pliable as the loamy dirt I crumble in my fingers. Can I roll this stone away? The response is silent but obvious. I cannot bring myself to shape my lips to bring it into language. No, I am being invited into the deep, down some back-alley holy well where words no longer work like that. My eight-year-old told me this week that he thinks that the heart is made of three parts: Feelings, Lies, and True Things. It strikes me now that any of these could be a portal down into unsayable portions of our selves which need renewing. I imagine entering that underground river and that maybe rushing past I’d be lucky enough to grab some colorful deposits out of the earth, some crumbs of chalk to take back up with me and color my journey once I’m out again. Maybe that’s what happened in the Caves of Lascaux.

And when words finally do spill out, they sound like a million inexpressible thank yous, something like: praise be to God for All That Is! For earthy smells on our hands and flung across the yard! Praise be for the smell of the outdoor air in my sons’ hair again. Praise be for water, holy and wild. Many poets have tried to catch this moment. I call on brother Teilhard once again to proclaim something like:

Blessed be you, harsh matter, barren soil, stubborn rock: you who yield only to violence, you who force us to work if we would eat.

Blessed be you, perilous matter, violent sea, untamable passion: you who unless we fetter you will devour us.

Blessed be you, mighty matter, irresistible march of evolution, reality ever-born; you who, by constantly shattering our mental categories, force us to go ever further and further in our pursuit of the truth.

Blessed be you, universal matter, immeasurable time, boundless ether, triple abyss and atoms and generations: you who by overflowing and dissolving our narrow standards of measurement reveal to us the dimensions of God.

Without you, without your onslaughts, without your uprootings of us, we should remain all our lives inert, stagnant, puerile, ignorant both of ourselves and of God. You who batter us and then dress our wounds, you who resist us and yield to us, you who wreck and build, you who shackle and liberate, the sap of our souls, the hand of God, the flesh of Christ, it is you, matter that I bless.

-from “Hymn to Matter,” Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, who died on Easter Sunday, 1955.

As wonderful and beautiful as ever it was. Your writing brings us all to springs ever gushing and yielding life. Thank you.